A Desert Stroll

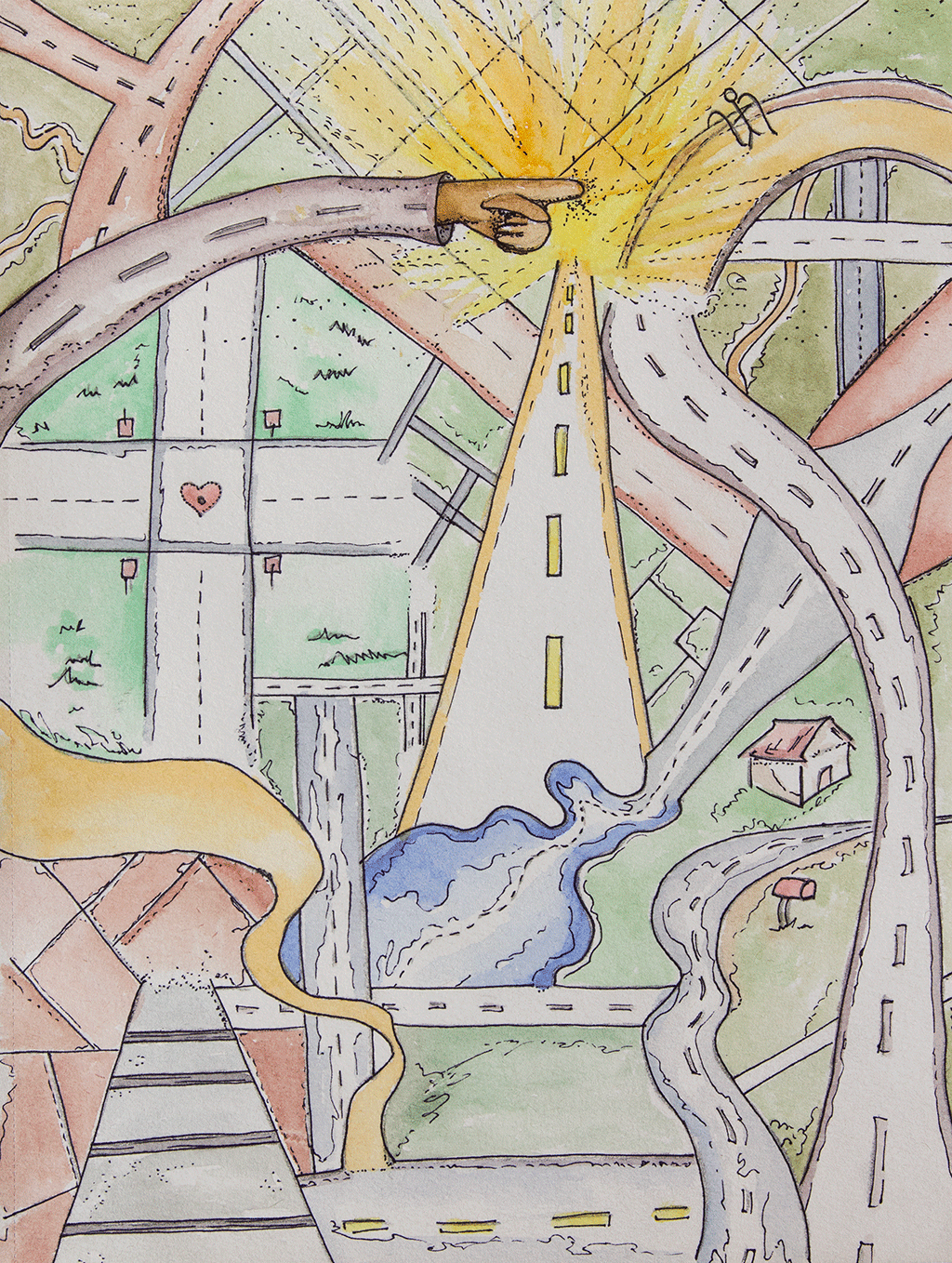

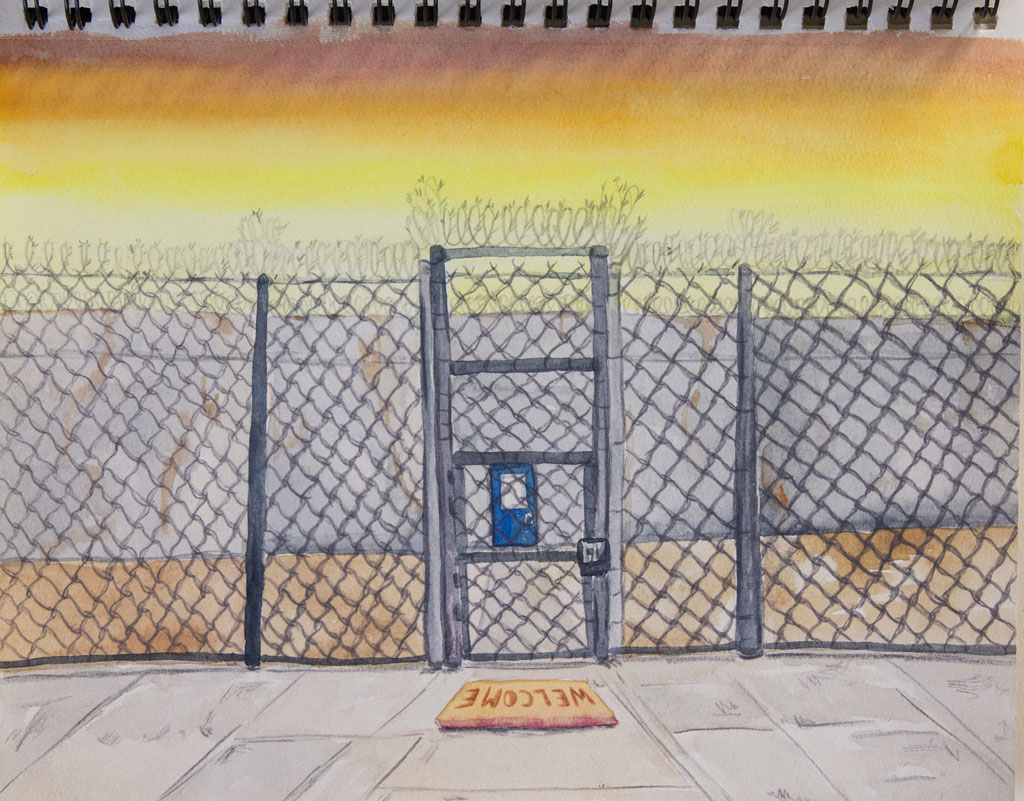

On a first walk through the gated compound, there’s no shaking the starkness of nothingness, a blank prison canvas. Marked by concrete and wire, there is no color, no personality. Numerous cinder block buildings are connected by concrete “roads.” Most days are idle and left to one’s imagination. The typical day revolves around the 3 chow times, several lock downs for count and limited programs.

Starved of Their Identities

The prison environment for inmates coupled with a history of trauma, losses and mental health crises becomes a breeding ground for decompensation. From Misluk-Gervase’s (2020) article about art therapy and the malnourished brain in individuals with anorexia nervosa, this art therapist realized I witness mental health malnourishment every day as male inmates are starved of their identities.

Focus of Clinical Attention

From the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5), a list of “other conditions” are provided that may be a “focus of clinical attention.” These additional issues are beyond mental health disorders and “may affect patient care.” The DSM-5 lists code Z65.1 as “Imprisonment or other incarceration” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, the desert of incarceration is recognized as problematic to patient wellness.

Malnourished Redefined

So, what does malnourishment look like? Marked by the effects of physical malnourishment, individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) often are rigid in viewpoints, resistant to treatment, lacking in emotion, have increased suicide risk, strained connection with others and trauma histories (Misluk-Gervase, 2020). As expressed in the corrections setting, inmates often have inflexible opinions which culminate in violence with no regard to consequences. Incarcerated persons often refuse treatment convinced they either don’t need help, or no one can help them. Further, to cope in prison, inmates may acquire maladaptive responses to emotion, or rather the lack of emotive expression or identifying emotions. With years behind bars, inmates often cope by “staying to myself” and not sharing with others furthering a decline in prosocial behaviors.

Toxic Stress Consequences

The compassionprisonproject.org (2021, as cited in Merrick, Ford, Ports, & Guinn, 2018) looked at Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in the inmate male population and found a higher incidence of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect, domestic violence, substance abuse, parents living apart, mental illness and having a family member incarcerated as compared to the U.S. population. These experiences change brain chemistry with the unstable, dangerous prison life contributing to functional decline. For inmates that have been incarcerated several times, the pattern of being “institutionalized,” whereby the engrained structure of prison life makes reintegration into society increasingly difficult. Sadly, many convicts may reoffend to return back to prison, to return to “what they know.” Prison living can be a starvation of self, slowly over time.

Research has determined that physical malnourishment impacts 9 distinct areas of brain functions including: overarousal to perceived threats; compromised access to long-term memory, distorted view of self; inhibited social connection with others; impaired decision-making; the brain cannot order their needs introducing myopic views of self and surroundings; rumination on details and facts to the sacrifice of one’ worldly perspective; perfectionism and compulsory actions; and seeking out pleasure despite negative consequences (Misluk-Gervase, 2020).

Of course, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa in not a typical consideration within mental health evaluations in prison. Inmates are not typically affected with significant weight loss as found in AN. However, what is the significant loss of self?

Art Therapist with Conviction

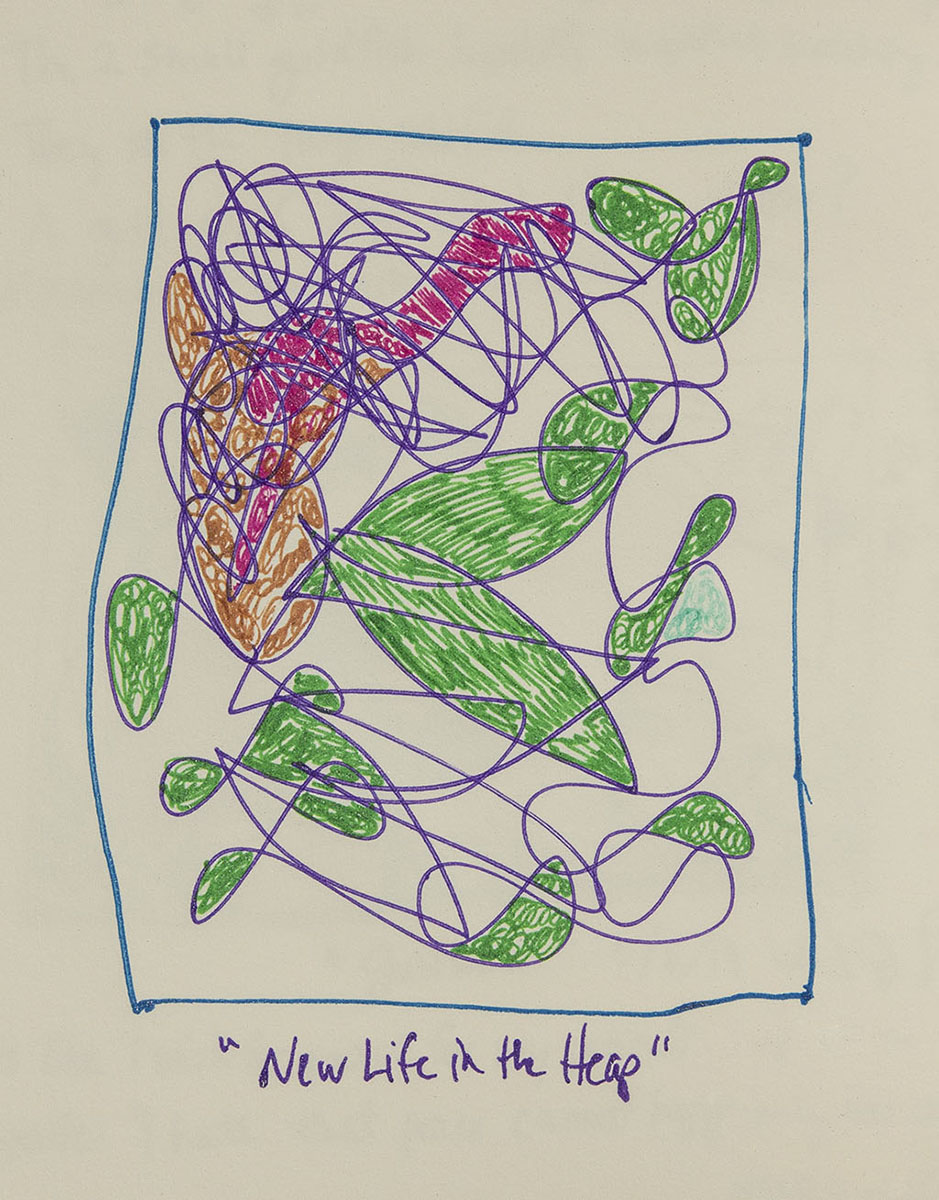

Through my art therapist lens, I witness the need for inmates to reconnect with who they truly are. Inmate Jones* had served 12 years of his 25 year sexual assault crime. In his first session, we completed a mask project. With identity teed up, he indicated looking forward to meeting again and would like to share his story next time. With therapeutic trust in place, the inmate shared his story, a story he never shared with anyone all these years. He realized the night of his crime was not just one night fraught with bad decisions alongside his heavy cocaine use. Rather, he realized he had not been living right for several years. This night has haunted him, especially with the victim and her family extending forgiveness. Hinging on his frustration, I suggested to consider “Who are you now?” and “What would it be like to accept this gift of forgiveness?” “How might it help the victims and yourself to know that healing can happen and new purpose can be gained?” I plan to have him create and bear his gift in the next session.

Presenting as depressed and downtrodden, Inmate Smith* came into session carrying a folder. A careful eagerness flashed across his face, “Can I show you some artwork?” With delight, we spent the session reflecting on his detailed work. With precision, his favorite image was a diagram of his home with all its dimensions, contents, complete with plants and items in the yard. He yearned for a return to home with his partner, yet was pitted with the idea that he may not have either to return to. For, it has been over a year since he has received any news on either. Tormented with pain, he sensed the worst has happened. Holding the space through images brought order to his thoughts. His ambivalence about living was soothed by feeling heard. Reconnection to who he really is… became the heart of his healing path.

Art Therapy Reflection

In my reflection, I created an image and poem, “Myself Masking.”

Cracked and barren

Lay the same old, same old

Gasping and dried

Knees sunk in the hot sand

Hunched and aching

My eyes tracking forlorn

Chained and uniformed.

Thirsty and starved

Crawl the same old, same old

Ain’t no way back

With cracks so wide and deep

Secrets hidden

Body, mind, soul revealed

Would get me killed.

Held and straining

Pushing down all the pain

Seeing myself

As I am now today

Only fleeting

A moment, a flashing

Myself masking.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Compassion Prison Project. (2021). How common are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)? Retreived from https://compassionprisonproject.org/childhood-trauma-statistics/

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011-2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

Misluk-Gervase, E. (2020). Art therapy and the malnourished brain: The development of the nourishment framework. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 38(2), pp. 87-97.