The Puzzled Look

With the inmate patient sitting across from me, I begin our session by simply asking, “I’d like you to draw a road” from Hane’s (1995) Road Drawing. The look of astonishment is priceless with reactions as raised eyebrows, widening eyes, relaxing shoulders, perplexed head tilts and more. Inmates often do a “say what?” moment to clarify, “ya want me to draw… a road?” or through the barrier of face masks during COVID-19, inmates state, “did you say a rose?” (I’m surprised to learn that many inmates have perfected flower drawings.) With a matter-of-fact demeanor, this art therapist responds, “Yes, a road. What shapes are roads?” Then we discuss potential ideas of what roads look like. Next, a purposeful pause is put into place. For a few minutes, I witness the artmaking process start with silence held while mark making commences. Moving away from talk therapy approaches, the inmate is doing something. From unspoken quiet, all that is heard is the scratching of pen to the paper, a welcomed break from the dorm. No awkward stares, no needed scripts, just image making.

Drop the Pencil

Many times, I witness what I call a “classic road drawing,” that is, a stereotypical two vertical or horizonal lines with a dashed line in between, centered on the page, with a forceful drop of the pencil signaling, “I’m done.” With compliance, many inmates complete the task with an unspoken, “I’m in, but not sure what this is all about.” To encourage development of their road I may ask about details to consider adding or changing. Or, I encourage them to take as much time as needed with a reminder “no high art needed today.”

Get on With It

Per assessment requirements in prison, there’s also a need for the counselor to complete paperwork alongside witnessing the work unfold. As this art therapist covers the token questions of hours of sleep and eating occurrences, disciplinary reports, gain time and more, the inmate responses become more natural and relaxed. By starting with artmaking, both inmate and art therapist are eased into the experience which sets up the foundation for therapy to occur.

Something to Talk About

At session end, I ask an “oh by the way, how did your road [drawing] come out?” Using the formal elements of art, that is, the language of art, we explore the image through the use of line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement. With healthy distance, we witness the image together as a snapshot of time and begin to dialogue with the road. Here’s some conversations about the road drawings:

Sidewalk With a drawn sidewalk, an inmate speaks about his experience as a “concrete man” describing the critical need for expansion joints to prevent cracking. His sidewalk turns into a road. Looking like a ladder, the inmate acknowledges, “I’m at the very bottom but there are supports.” We then discuss what it would be like to climb the ladder and what supports could help you as you get higher. How might adding joints in your life allow you to grow? How do you make sense of this? The inmate states, “for these 10 years (his sentence), I need to stay positive and stay on the right path.”

Rainbow Bridge In another image, an inmate draws a large half circle bridge crossing a river with a bright smiling sun and clouds in the sky. He looks at the images and acknowledges, “freedom, when I’m on the other side.” He observes his large bridge needs some supports like railings and a sidewalk.

Multi-Lane With this multi-lane road drawing, this inmate describes the left lane as the “right way.” The “wrong way” to the right has less lines in it with many other roads. The inmate states, “The bad side is easy. It’s so easy to veer off that way.” This art therapist notes the “right road” literally moves in the opposite direction to the left possibly suggesting the confusion of making positive choices.

Country Meets City In this image, the inmate depicts a country road horizontally and city road vertically making a perpendicular intersection with the country road on top. This young 22-year-old conveys his ambivalence about wanting to return home to the country but desires to see a bigger place. The image begs the question, “Will he go back to his old ways or jump onto the on-ramp?”

Widening With a rocky start, this inmate describes a curvy narrow road that is straightening out. He later edits the road to widen it at the end because, “that’s the future” and he is pleased. When asked what advice he would give himself over this 10-year sentence, he stated, “Take your own, day-by-day.”

Hometown Map This inmate states he will be moving out of this state when he gets out. Drawing a map of his community, he depicts neighboring thorough fares and homes in extraordinary detail. He later reflects on the image saying, “I’ll get there,” and I state, “But I thought you said you were moving out of this state?” A flash of sadness crosses his face.

Parroting On this occasion, I mimicked and drew the inmate’s drawing as he was drawing it. I asked, “How is it for you to draw?” He replied, “Like I’m not in prison” and I retorted, “Then do that!” He labeled the parts of the road as “wide,” “narrow” “loops,” “straight,” and “not wide, 2-way street.” Then, I showed him my version of his road and asked, “wonder what it would be like if water flows down this road?” We discussed how water is fluid, forgiving, and flexing. From motivational interviewing and positive psychology perspectives, the inmate’s positive coping skills were reinforced. Most important, the inmate received a needed message from his created image.

After discussing a road drawing, there seems to be a cathartic release, yet amazement about how “dead on” their road seems to be telling a message most needed. I acknowledge how this image could provide a pulse check today. “How am I this day? Where is my mind? How does the image inform me about my journey? What do I need? How might I better take care of myself now in prison to prepare for life on the outside?”

Art Therapist with Conviction

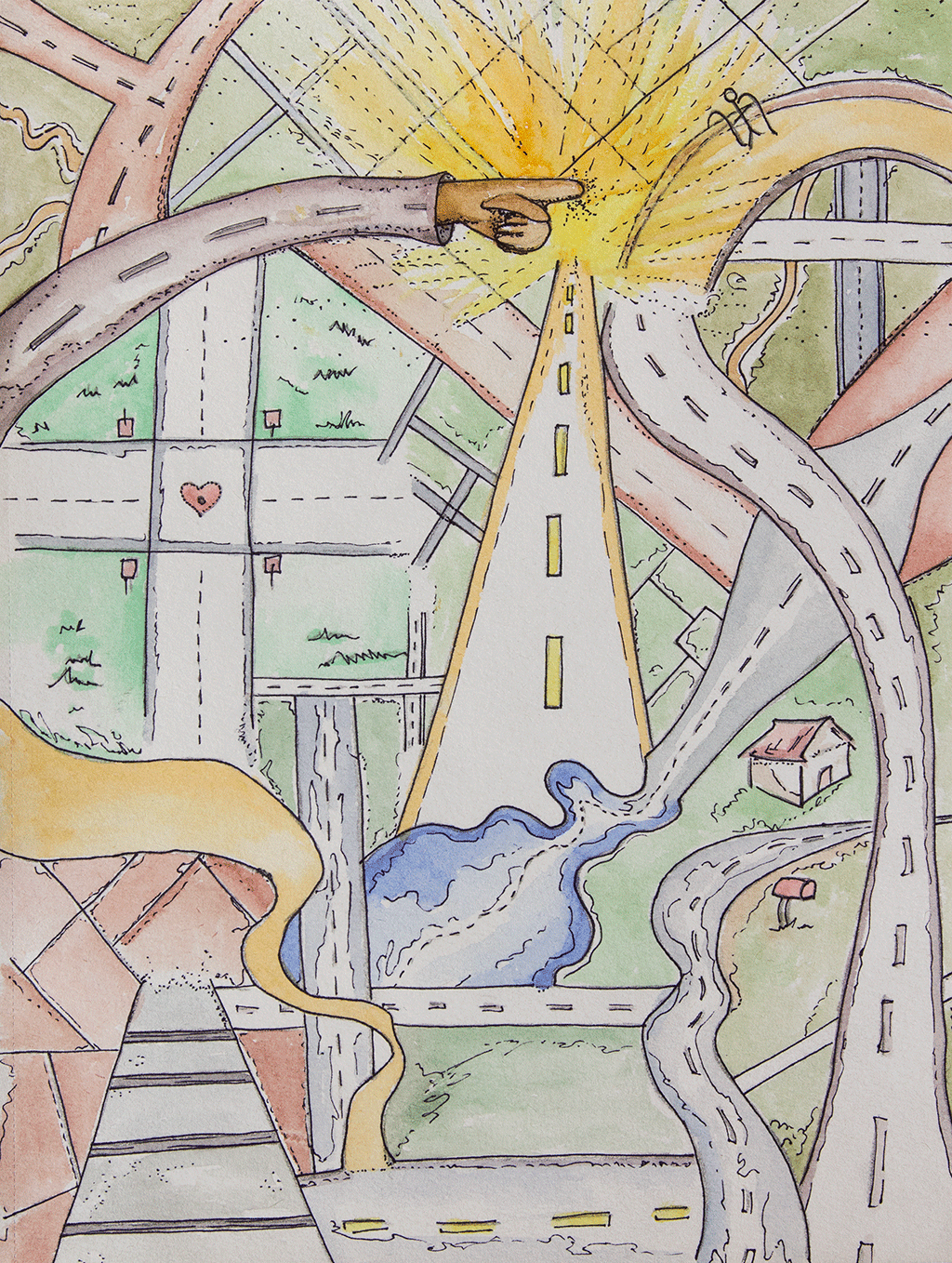

Reflecting upon these inmate road drawings, I imagined what it would be like to “fly over” these roads. Looking down from a bird’s eye view, I created an image and poem called “Ribbons of Concrete.”

“Ribbons of Concrete”

Ribbons of concrete

Buckle up that seat

So many roads

That you will meet.

All within this tiny grid

Just thinking ‘bout all they did.

Going straight

Not gonna hate

At crossroads

For a right turn

Hope I don’t get burned

And wind up again

With time to ponder

Plan and wonder

How to return back

To a widening path

Lit up by no more wrath.

From a positive art therapy approach, Wilkinson and Chilton (2018) asserted many benefits of focusing on patients’ strengths to achieve therapeutic goals. Recognizing an inmate’s strengths moves away from the medical model “what’s-wrong-approach.” An inmate’s identity can be strengthened by moving away from “my diagnosis” or “my history” to “my action.” Rather than prescribing targeted coping skills, artmaking demonstrates an inmate’s inherent capabilities in action. This process of self-care in-the-now of artmaking is witnessed and affirmed by this art therapist.

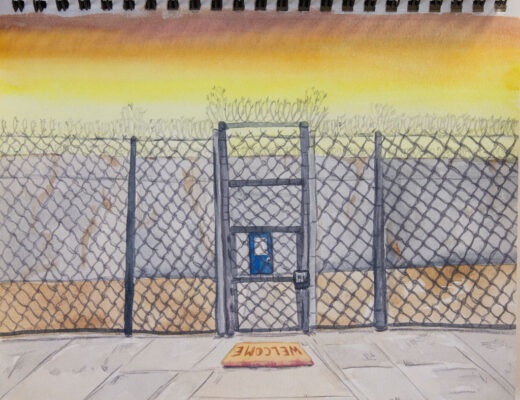

Roads provide a simple and approachable means for inmates to engage in artmaking (Hanes, 1995). As symbols of movement, time and direction, road images get to the heart of the matter: “Who am I? Where am I now?” Gussak (1997) pointed out, “possibly unbeknownst to the correctional staff, the inmates in prison have already ‘escaped by putting on masks’ ” (p. 68). As an art therapist with conviction, I bring up these protective masks as purposeful for safety but in no way suggesting who they really are. These ribbons of concrete, a myriad of roads, provide a welcome invitation: inmates can pause and be reminded of who they really are behind these walls.

References

Gussak, D. E. (1997). Drawing time: Art therapy in prisons and other correctional settings. Chicago: Magnolia Street Publishers.

Hanes, M. J. (1995). Utilizing road drawings as a therapeutic metaphor in art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, Rehabilitation, and Education, 34(1), 19-23.

Wilkinson, R. & Chilton, G. (2018). Positive art therapy theory and practice: Integrating positive psychology with art therapy. New York: Routledge.